There has always been a need in healthcare for blood replacements. According to medical folklore it is thought that the Incas were the first civilization to use blood transfusions as a healing procedure. The methods used are unclear but they were somewhat successful (official numbers unknown) due to the fact that a large part of the indigenous people in the Andean region would have the same type blood making the risk of fatality far less.

For the European population it was a somewhat different story. It took centuries of experimenting, research, trial and error as well as numerous fatalities to finally reach to the safe and life-saving procedure we know of today.

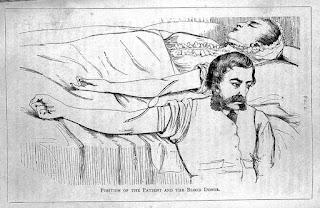

|

| Source: Wellcome Trust |

In 1628 the first progressive step was made by William Harey, a British physician, when he discovered the circulation of blood and started carrying out transfusion experiments on animals. However, it wasn't until 1665 when the earliest known successful blood transfusion occurred in England when physician Richard Lower kept a dog alive by transfusing blood from other dogs. This animal-to-animal experimentation would lead to the next step of successfully transfusing animal-to-human blood.

Experimentation continued and in the early 19th century, British obstetrician, Dr. James Blundell, made efforts to treat hemorrhage by transfusion of human blood using a syringe. In 1818 he went on further and performed the first successful transfusion of human blood to treat postpartum hemorrhage. These early transfusions were risky and many resulted in the death of the patient. By the late 19th century, blood transfusion was regarded as a risky and dubious procedure, and was largely shunned by the medical establishment.

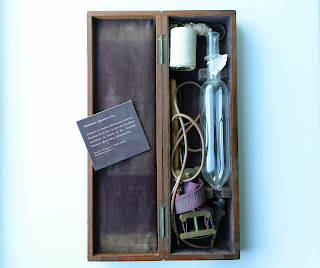

|

| Source: Wellcome Collection |

In Ireland, the first ever human-to-human blood transfusion was carried out in April 1865 in Jervis Street Hospital, Dublin by Robert McDonnell (LRCSI and President of RCSI). The case was a fourteen year old girl, Mary Anne Dooley, who was brought in after a workplace accident in a paper mill, in which her arm was torn and lacerated. In a final attempt to save her life Robert drew 350 millilitres of blood from his own arm, stirred it, strained it and syringed it back into Mary Anne. The girl improved but only for a short time, and ended up dying the next day. McDonnell was such a champion of the procedure that he designed his own blood transfusion instrument which is today kept in RCSI Heritage Collections.

|

| RCSI/MI/224 |

|

| Robert McDonnell (1828-1829) |

Blood transfusions were finally given the recognition they deserved in 1901, when Austrian Karl Landsteiner discovered three human blood groups (O, A, and B). This discovery completely transformed the procedure and helped it finally achieve a scientific basis and become safer. Landsteiner discovered that adverse effects arise from mixing blood from two incompatible individuals. His work made it possible to determine blood group and allowed blood transfusions to take place much more safely. For his discovery he won the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine in 1930; many other blood groups have been discovered since.

Today blood transfusions makes it possible for many people to lead normal healthy lives. Every year thousands of patients require this vital procedure in hospitals, because they are undergoing surgery, recovering from serious illness or have been in a serious accident. Over 1,000 Irish people receive transfusions every week in Ireland. Unlike the early years of its development, blood transfusions are now very safe and in many instances can be lifesaving.