Halloween has its origins in the ancient Celtic festival of ‘Samhain’, one of four seasonal turning points in the Celtic calendar. Samhain marked the end of the harvest season and the transition from ‘light’ half of the year, associated with life, to the dark half of the year, associated with the dead.

Samhain, with its influence on modern-day Halloween, symbolises a weakening of the lines between this world and the next, and between the realms of the dead and the living.

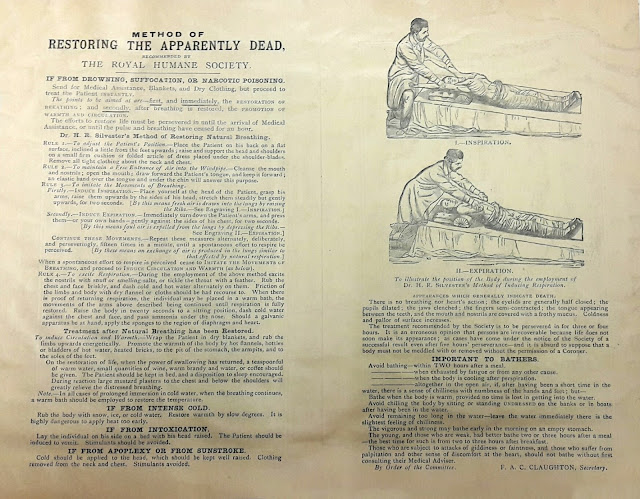

But what exactly does it mean to be dead, and when does ‘death’ actually occur? These were just some of the questions that physicians in the late 1700s grappled with in their quest to ‘reverse’ death through the application of resuscitation techniques.

|

| Royal Humane Society pamphlet promoting resuscitation in the case of apparent drowning victims, c1860 |

Definitions of death and ‘The vital force’

While the scientific and legal definition of death continues to cause debate to this day, the blurring of boundaries between the living and dead was, until the eighteenth century, compounded by an incomplete understanding of the physiology of the human body.

The mechanics of breathing and the anatomical structures and relationships that support pulmonary circulation were well established by late 1700s. However, while it was widely accepted in medical circles that the inhalation of air was critical to maintaining life, the physiological process of respiration remained a mystery.

Lacking the knowledge of chemistry to explain the role of oxygen in the body, physicians and philosophers alike for many centuries had attributed what we now know to be the mechanism of gas exchange in the body to a kind of metaphysical ‘spirit’ or life-giving vital force.

The metaphysical and elemental nature of this ‘vital force’ combined with an absence of clear consensus on or definitive understanding of the markers of clinical vs biological death suggested a kind of permeability between the state of being alive and that of being dead, or ‘apparently dead’.

The ‘Apparently Dead’ and resuscitative intervention

While accounts of resuscitation attempts may be found in literary and artistic works stretching back several thousand years, a fresh wave of interest in new and improved methods of resuscitation emerged in the late 1700s. This was prompted in part by scientific discovery and the quest for knowledge characterised by the Age of Enlightenment. On a far more practical level, however, this resurgence of interest in the art and science of resuscitation was heavily influenced by the increased number of drowning deaths in the waterways and ports of Europe’s major towns and cities and, specifically, the emergence of ‘humane societies’ in considerable numbers across Europe in response to this.

Humane societies aimed to reduce instances of death by drowning by promoting resuscitation as a means of medical intervention for ‘apparently dead’ victims. Humane societies asserted that any member of the public who might happen upon an apparent case of drowning should have access to the requisite knowledge and equipment to carry out resuscitation in the absence of trained medics or physicians.

Education and awareness was therefore at the core of the societies. They promoted the message that death – at least by drowning - was not absolute, and that passers-by had the power to keep the ‘apparently dead’ from joining the ranks of the actually dead through the application of suitable resuscitative techniques.

Crucially, humane societies also incentivised resuscitative intervention by members of the public with financial rewards. Acts of courage and bravery were publicly recognised and monetary sums and medals frequently awarded as a means of inspiring others into similar acts of valour.

|

| Plate illustrating the resuscitation of a drowned woman using a tobacco smoke enema apparatus. Source: Wellcome Collection |

Resuscitation techniques in the eighteenth and nineteenth century

How might a member of the public stumbling across an ‘apparently dead’ drowning victim along the banks of the Thames in eighteenth or nineteenth century London be expected to respond? What kind of resuscitative techniques were they supposed to employ?

The standard manual method of CPR (cardiopulmonary resuscitation) as we know it today – comprising rounds of chest compressions combined with mouth-to-mouth/rescue breaths – is a fairly recent addition to standard medical practice and first aid, having only been widely adopted since the 1950s.

Though mouth-to-mouth resuscitation was practised before this point, it was widely regarded as vulgar and unhygienic. This was especially true in Britain, where it fell out of favour as a recommended method of resuscitation by the humane societies in the nineteenth century and many physicians and other medical professionals refused to perform mouth-to-mouth on patients.

Pamphlets, advertisements and public notices promoted a range of resuscitative techniques that might be used to restore life to the ‘apparently dead’ in the eighteenth and nineteenth century. This literature frequently called for ‘agitation’ to stimulate the heart and lungs back into action. This could mean anything from vigorously shaking or rubbing the patient to rolling him or her down a small hill, though later methods tended to advocate a sequence of gentler manipulative movements such as raising the arms that would replicate the action of breathing. The use of smelling salts was advocated to trigger inhalation, while the application of large mustard plasters was recommended to encourage circulation and warmth in patients who may have been submerged in cold water for some time (following the logic that mustard seeds themselves were hot). Spirits might be applied to the patient’s wrist or neck, or bloodletting used to stimulate blood flow.

While most resuscitative techniques relied on external stimulation of the patient, tobacco smoke enemas were promoted as a means of stimulating the interior constitution of drowning victims until the mid-nineteenth century. In London, the Royal Humane Society installed tobacco smoke ‘fumigator’ kits at regular intervals along the River Thames with instructions for use by any passers-by who might witness a drowning in progress.

We’ll take mouth-to-mouth any day of the week.